I first need to thank everyone who said nice things, spent a moment to grieve with me, or simply took the time to read my remembrance of Duncan. I mostly write in my own little corner of the universe and I’ve gotten much more in response to it than I could have expected. And I thank you all for that.

It’s also been helpful, since, after mostly getting past the flu, I’ve spent the last few days getting over…something. I don’t know if it’s remnant flu or something new, but it’s definitely gotten in the way of my having thoughts about anything.

Except for one odd dream, anyhow, where I was playing bass in a band with Paul McCartney and Kevin Gilbert. While I remember the dream, I do not, unfortunately, remember any of the music that might make me either the most famous songwriter of the last 60 years or an underappreciated legend of the 80s and 90s.

When You Are Wrong About Everything

All this means that events have outstripped my ability to comment on them. During the Russian semi-coup, I was trialing thoughts about how it might end up like the Turkish coup in 2016, helping the central government purge the country of anything but the most fervent loyalists (though with less local interest in the Poconos). Like everyone, I was also working on a trial balloon connecting it to the Russian Revolution, an ongoing war, and the effects of a worldwide plague. And then everything took its own path and I ended up not being right about much of anything. At least I am not alone in that regard. And I don’t think that story is over yet.

OceanGate

I’m wading into something that seems to irritate everyone, but I think there are at least four distinct points about the OceanGate submersible tragedy that are worth making. First, it is actually a tragedy. When people die who aren’t actively engaged in harming humanity, it is sad. In my estimation, it is not a waste of public resources to try to save and/or recover other people, nor is it wrong to at least try to generate the best information about the situation we can, even if those other two things are not possible.

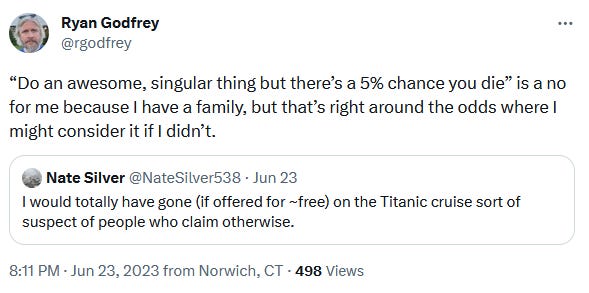

Second, people kind of lost their minds about Nate Silver’s tweet:

I think my fantasy leaguemate Ryan had the only response that didn’t seem way out of proportion:

For me, the “awesome, singular thing” would have to be even more remarkable than a Titanic trip for me to do it if I were a single guy with...I dunno…a 1% risk of dying. So he’s more intrepid than I am. It does seem to me as though being able to get that deep into the ocean and seeing probably the most iconic ocean wreck in human history would be worth it at some level. But I’m a cheap bastard, so probably something like 1-2% of annual income at a risk that’s maybe 5x plane travel. Which puts me at something like 4 billionth in line for this particular adventure.

Third, and sort of related to both the above point and the next, there is a sense in which these very wealthy VC and startup guys seem to be getting awfully high on their own supply. Elon losing a massive amount on Twitter is getting a lot of attention lately, but Calcanis and Balaji and Andreesen and Khosla and…a much longer list of these guys, seem to think that they are the pathbreakers for all the rest of us and that any inconvenience for them (say, a small banking crisis) must be addressed with maximum alacrity and force. I know this sounds like it differs from my first point, but I don’t think it does—these geniuses need to get in line with the rest of us or solve their own effing problems. And so I do get the frustration with someone who flaunts his disregard for safety, especially in a business that is, by definition, extremely dangerous. The idea that all this happened because the company was “woke” is moronic. Speaking as a white 50-year-old guy who has spent his time in tech, what you are seeing is a soft ageism that is incredibly common in the startup world, not whatever amorphous racist crap these guys are trying to foist on the world. At least Stockton Rush—and old white guy—very literally had his skin in the game.

Finally, my thoughts are largely of a piece with Tim Burke’s and Kareem’s. While I just noted above that I don’t think deploying resources to help others is a bad idea (to the contrary, that seems to me to be the point of having public resources), even a cursory comparison between the coverage of—and resources allocated to—the OceanGate submersible and the sinking of an overloaded trawler in the Mediterranean would seem to suggest that there are groups of people who we allocate more to—more attention, more expense, more of the public purse—and I do take issue with that. Tim Burke makes a fantastic point about how people tend to frame this:

If it’s not just money and power, what else is it? In a deep sense, I’m going to say the difference is about subjects who are understood in terms of social science versus subjects who are understood in humanistic terms. Who is a policy problem and who is a human being? We perform that separation almost instantaneously, unconsciously. It’s deeply encoded in our informational infrastructures, in our habits of mind, in the training of our senses. What anonymous person do you look at and imagine a story for, where you use clues of appearance and affect, of observed behavior and overheard snatches of conversation, to compose an imaginary biography? And what person do you look at and think, “Somebody needs to do something about that situation” or think about that person as a job or a function or a situation—as a thing?

The Aylan Kurdi picture from 2016, which I will only link to because it absolutely breaks my heart to look at, drew a great deal of attention to the issue briefly, but not in a way that seems to have been durable. I was the father of a two-year-old boy at the time, so it took me absolutely no effort to understand the crisis in a very personal way. That seems not to have made it to those at the crucial points of decision and any time we lack sufficient humanity, we are made poorer as a people. And this is not just one tragedy, but hundreds.

I Don’t Know How Much Light Was In Those Ages

The Bright Ages by Matthew Gabriele and David Perry was one of the big texts in my orbit from the last few years. So, too, is Slouching Towards Utopia by Brad DeLong, which I am about halfway through at the moment (I will probably talk more later, but I am enjoying it quite a lot). I have been reading Perry’s public, more journalistic pieces for coming up on a decade; Gabriele for not quite as long, but I will pay attention if I see his name pass across the transom. I have been reading DeLong for almost as long as his old blog has been around. My recollection was that this goes back to 2002 and was an impetus for my restarting some online writing when I was in grad school. I have been reading DeLong’s podcast partner Noah Smith for several years, probably a little longer than Gabriele, not quite as long as Perry.

I like all four of them, but they are not especially fond of each other, it turns out. As far as I can tell, the jumping off point was DeLong saying that he didn’t like the book and was rubbed the wrong way by the argument that Rome did not fall. After a couple of Noah Smith tweets, Gabriele and Perry put together a dismissive Substack post of Smith and DeLong:

DeLong responded in kind:

Cards on the table, I didn’t have prominent public intellectuals having the effing “The Holy Roman Empire with neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an empire” on my Bingo card for this month. And I like them all and am less qualified to comment on this than any of the four of them, since I haven’t tried to practice even the very different kind of economic history I once did in 18 years. But I am clearly failing the “discretion is the greater part of valor” test today, so will make a few points.

DeLong and Smith dedicated their most recent podcast to this and it’s actually a smarter, more circumspect version than the arguments to this point, but DeLong is insistent that identifying the Dark Ages as lasting past ca. 800 is a category error and that you are now lumping Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages together. If you were going to stick a gun to my head and ask me to periodize, I would agree. But that doesn’t mean that the world agrees. Indeed, it seems to me that Petrarch identifies the Dark Ages as having lasted very nearly to his present day. It appears to me that this kind of periodization (5th-14th centuries) is more common; indeed, the first several times I encountered the concept of the Dark Ages, it was more or less overtly pegged to ca. 500-1500 (I guess someone was trying to make it really simple to remember) and it wasn’t until my study of history got a little more serious that I came to think of that as being wrong. But Gabriele and Perry are not engaged in a slight of hand, as Smith suggests in the podcast, by talking about, say, the 12th century in the context of the traditional understanding of the Dark Ages. It’s all well and good to say that the Third Century is the actual Fall of Rome or that it starts at the end of the period of the Five Good Emperors, but the argument that exists is not just about whatever physical evidence you can muster, but also about what is now one of the oldest issues in historiography. I suspect that’s a big piece of Gabriele and Perry saying that DeLong and Smith need to do the reading.

On the other hand (now I’m an economist!), there is absolutely a thing that is happening during the time frame ca. 180-800 which needs some kind of description. It does appear that Mediterranean trade is much diminished, the political seat of the Roman Empire moves from…Rome…to Constantinople, the populations of the largest cities decline, the objects that we would have identified as the high culture of Greece and Rome (aside from churches, anyhow) are less produced less often, the rate of progress in engineering slows, and so on. Early in this time frame, Rome starts losing pieces of its empire, the Germanic tribes form and finally start to repel the Romans, the Han Dynasty falls, and the Sasanian Empire is constituted. It’s a different world, more fragmented, with profound economic consequences. DeLong gives measures of these things—and examples from the literature—and while they are, to some degree, estimates, they aren’t meaningless, and I think it’s fair to ask Gabriele and Perry to at least do enough reading to understand where the numbers come from if they are going to dispute their significance.

Even if we take just the period to Charlemagne as our focus, there is still plenty of action. At the beginning of the seventh century, Islam doesn’t exist; by the end of the eighth, the Umayyad Caliphate stretched from the Indus River to the Iberian Peninsula. You have the whole of the history of the early Christian Church—I will periodically remind my wife that her family name is that of one of the great losers in history. There is a fascinating multipolar diplomatic history between Rome, the Germanic tribes, and the Huns. The Tang Dynasty stretches its legs far enough into Eurasia that the Huns, the Umayyad, and Byzantium have to pay attention. Near the end of this window, you get the ascent of the Norse—and the Vikings have always captured the imagination. We do lose a certain connection to some kinds of source material, and that is important. It also seems important that the social and cultural history suggests that the interiority of the lives of these various groups have elements of kinship, culture, and religion that provides significant meaning, even if we recognize that the material conditions for at least the top third of the population would be much impoverished if we were to compare them to the peak of the Roman Empire.

This is all a high school-level reading of events, I understand. But my sense is that this is mostly a discipinary thing. For the record, I think DeLong is literally the least EconoBro economist that I can think of. Smith and Perry, as much as I like both of them, have elbows when they write. The most irritated I get with Smith is typically in these kinds of situations, where some historian says a thing that he doesn’t agree with that isn’t grounded in quantitative data, and he can be kind of an a-hole about it. He is also kind of neoliberal and does some hippie punching, which appears to be high up the list of annoyances for Gabriele and Perry. On the other hand, if Gabriele and Perry didn’t call Smith a racist, they at least implied that he was doing a racism by saying that Rome fell and I, too, would get a little pissed off if someone implied I was a racist for putting a contested description on my interpretation of the data.

There is a thing here if you are a civilian that is worth knowing. A large portion of the categories and descriptors we use in history, especially pre-modern history, were not a part of the language used at the time. The people we think of as the Byzantines though of themselves as Romans, full stop. Byzantium and/or the Eastern Roman Empire would have meant nothing to them. The idea of the “Dark Ages” begins with Plutarch in the 14th century. The word “Feudalism” would have meant nothing to an inhabitant of 11th-century France. There are a million of these and they often have descriptive utility to us in understanding the past. But, when thinking like a historian, you should try to understand what they help us understand and what parts of history they occlude.

We Are Going To End This With Fun If It Kills Me

Four items:

#1: Loved this bit from Neko Case’s latest post:

My favorite thing I’ve learned is the term for the fascinating style of singing-speaking that you know about but have maybe never heard the proper “write it down on paper” term for. I know I didn’t! Only the German language seems to have the syllables to name it, it’s called “Sprechstimme” pronounced “sprek-shtimm-e.” It’s in my top 10 favorite words for sure. It’s pretty much speaking with momentum and/or cadence and launching in and out of melody. Rap music is rife with Sprechstimme as is opera. I love that those two genres go hand-in-hand as its biggest purveyors. Music is a small world in the best ways.

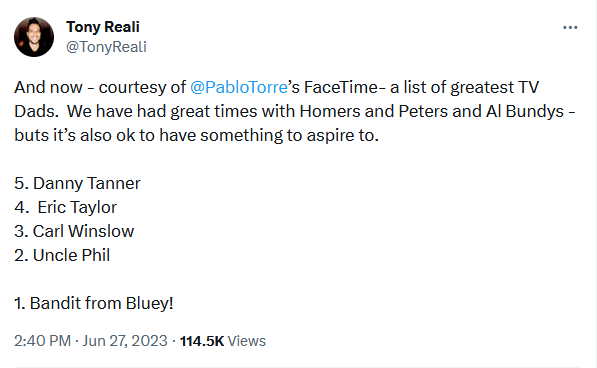

#2: This Tony Reali tweet:

To be clear, I believe Bandit sets unreasonable expectations for how much abuse a father should take. But he’s a model for all of us.

#3: I have to recognize Jo Adell hitting just a monster home run:

For a guy who has spent a few years being a kind of disappointment—one tied closely to the general frustrations of his organization—it’s nice to see him tearing it up in Salt Lake City and getting a moment like this.

#4: You might have already seen this, but if not, Rick Astley played drums and sang “Highway To Hell” in an iconic performance at Glastonbury, also doing a bunch of Smiths songs with Blossom. My Duck-Fu has failed me a little and I couldn’t find the full performance, so, instead, here’s your version from the Isle of Wight Festival:

If you’d have told me about this in 1987, I never would have believed you.